Summary

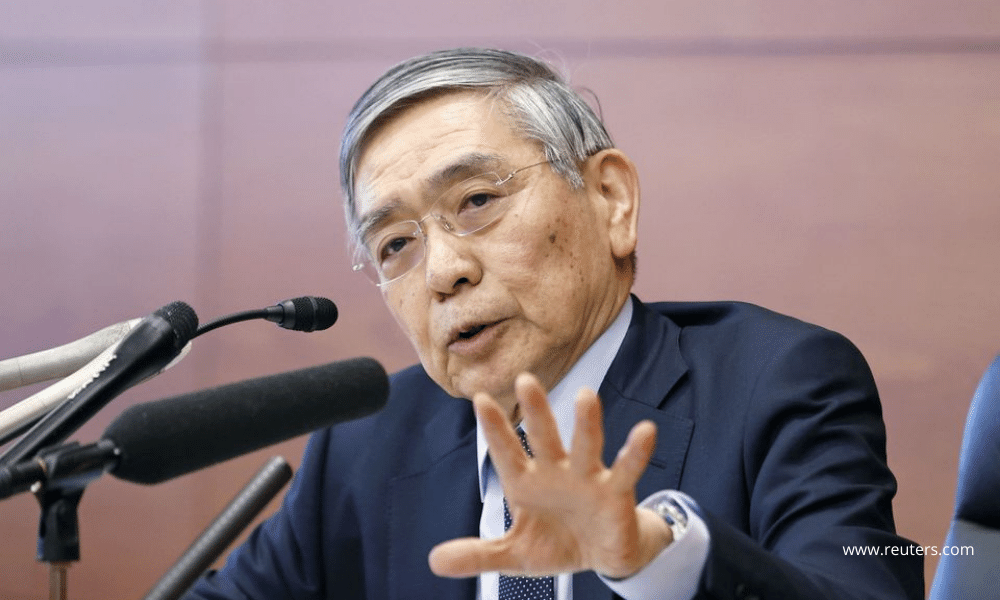

TOKYO, March 25 (Reuters) - Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda on Friday reiterated his view a weak yen benefits the economy as a whole, brushing aside concern the currency's slide to multi-year lows could do more harm than good to the resource-poor, import-reliant country.

Due to structural changes in Japan's economy, the benefit from a weak yen comes more through an increase in the value of profits companies earn overseas, rather than a rise in export volume, Kuroda said. "There's no change now to my view a weak yen is generally positive for Japan's economy," he told parliament.

The yen was headed for its worst week in two years, pummelled by Japan's rising import costs and ultra-low low interest rates. It fell to a fresh multi-year low of 121.84 to the dollar on Friday.

Kuroda said the recent rise in import prices was driven mostly by global commodity inflation, rather than the weak yen. While consumer prices may accelerate to around the BOJ's 2% target from April, the central bank is in no rush to withdraw stimulus as any increase in inflation must be accompanied by steady rises in wages, jobs and corporate profits, Kuroda said.

"Cost-push inflation that is not accompanied by wage hikes will hurt Japan's economy," by weighing on households' real income and profits of import-reliant firms, he said.

"As such, it won't lead to sustained achievement of our price target. That's why the BOJ will continue to maintain powerful monetary easing," Kuroda said.

Speaking at the same parliament session, Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki said the government will continue to keep a close eye on currency moves, including recent yen declines, and their impact on the economy.

"Exchange-rate stability is important, and sharp volatility is undesirable," Suzuki said, repeating his verbal warning against excessive yen declines. Kuroda also said it was desirable for currency rates to move stably reflecting economic fundamentals.

Such warnings, however, will likely have little effect in reversing a weak-yen trend driven by a hawish Fed, analysts say. "The more you do it, the less impact it tends to have," Jeffrey Halley, senior market analyst of Asia Pacific at OANDA, said of the policymakers' jawboning.

Some market players see the yen's decline as a sign of the erosion of the currency's status as a safe-haven. Recent data showed Japan recorded its second largest current account deficit on record in January as a jump in oil import costs offset gains in investment income, highlighting the economy's vulnerability to commodity swings.

"Up till now, Japan was able to stably issue huge amount of government bonds at low interest rates due to households' massive financial savings and the country's current account surplus," finance minister Suzuki said.

"There's no guarantee such market conditions will continue when we look at how energy price moves led to Japan running a current account deficit.